In these times of diplomatic standstill, when the end to the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territory seems as distant as ever, here are some heartwarming words, surprisingly, with respect to mass public transportation:

Strong words indeed; words that make it very difficult to uphold a land seizure order issued in an occupied territory for, at least at face value, the sole purpose of building a steel railway between two cities in the territory of the occupying country. One of the solutions the court found for this stumbling block was the state’s argument, quoted above, that the railway should be viewed as part of an overall steel railway system which, in future, would also serve the residents of the OPT. Though the court does discuss the position of international law in detail, as well as the state’s fantastical plans, it ultimately chooses not to make a finding on the question of whether international law has been breached in this case, since, as it claims, “the harm to the rule of law does not exceed the damage caused to the interests of the Railway, third parties and the public interest, should the petition be accepted despite the late submission”.[4]

How does the court reach the conclusion that the injury to the rule of law is minor? First, the court rules that the size of the land slated for seizure is very small. Second, the Israel Railway has made a serious effort to reduce the harm done to the petitioners: olive trees in the seized land were moved elsewhere, terraces were fortified, etc. Third, the petitioners were offered monetary compensation for the seized land. They were also offered mature trees that they could select themselves from a nursery(!). Fourth, the route was not planned with the intention of violating international law. All of this, the court argues, “indicates that the authorities acted in good faith and sought to arrive at an arrangement that would be consistent with legal provisions (without our addressing the question of the arrangement’s legality)”.[5]

The court’s message to the petitioners is: Why complain? The land that was taken from you is small; we have done everything in our power to mitigate and soften the blow; you have been offered compensation; and even if international law was ultimately breached – it was unintentional. We really did try to be good. As for the small detail of whether all this conforms to the law – we leave that for another time.

The Beit Iksa Bluff

Indeed, why get stuck on details? Why make a real inquiry as to whether the state’s fantastical plans have any footing in reality? Why wonder how it is that the state, which relentlessly encourages its citizens to repeat the mantra “They’re there. We’re here”, is promoting a plan to connect Israeli cities with cities in the West Bank and the latter with Gaza and Rafah? Why should the court, which has upheld the lawfulness of the separation wall time and again in dozens of petitions submitted to it, raise an eyebrow when it is presented with a plan that is dedicated to tearing down walls, regional peace and solidarity among nations?

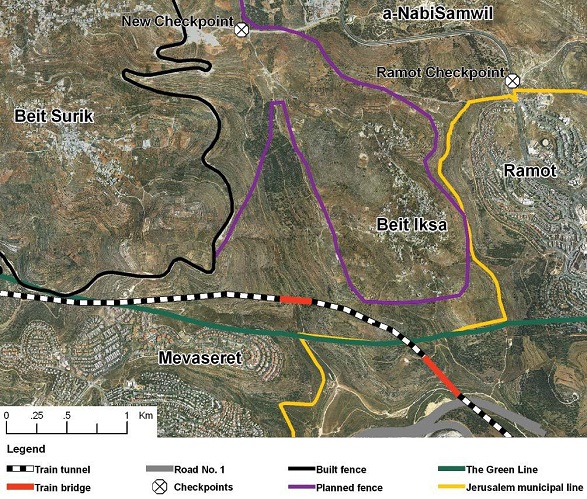

Let us take a closer look at the authorities’ good faith, as described by the court, and their aspiration to “arrive at an arrangement that would be consistent with legal provisions”. It appears that the original railway route was not meant to run through Beit Iksa land, but rather near Mevasseret Zion which is inside the Green Line. Once residents of the Rehes Halilim neighborhood in that community learned of the plan to build the railway near their homes and its expected interference with their quality of life, they submitted their objection to the planning and building authorities. This is how the current route came to be. It was only then, when the state realized there was a problem with respect to international law, that the new plan for a regional railway was hatched.[6]

Let us recap: the occupying power plans a railway line to connect between the two largest cities in the country; the route is planned to run near a community inside the occupying country; residents of this community file an objection and the route is shifted to the occupied territory; in order to have the railroad built, land that is privately owned by residents of the occupied territory is expropriated; finally, in order to have this move conform to international legal standards, a plan is concocted in order to demonstrate that the land seizure might someday benefit residents of the occupied territory as well.

Beit Iksa, the Green Line and the railway route. Source: Shai Efrati and Peace Now

Between Beit Iksa and Route 443

This judgment is, of course, reminiscent of Road 443 and the two famous judgments it wrangled out of the Supreme Court: Jam’iat Iscan Al-Ma’almoun and Abu Safiya. In Jam’iat Iscan Al-Ma’almoun, the court reviewed the state’s plan to seize land in the West Bank for the purpose of building a grandiose road system, the main element of which was the Ben-Shemen Atarot road which runs through the OPT.[7] In that case, the state argued that the roads were primarily meant to serve residents of the OPT. The Palestinian land owners who petitioned against the plan argued that it had nothing to do with benefitting residents of the OPT. The state denied this position, but did confirm to the court that “this plan is connected to planning inside Israel, it takes it into consideration and forms a joint project for Israel and the Area. It will serve not only the residents of the Area, but also residents of Israel and the traffic between Judea and Samaria and Israel”.[8]

Despite the state’s clear signal about the true purpose of the planned seizure, the court, headed by the then-Justice Aharon Barak (later Supreme Court President), rejected the petition and ruled that there was no cause to doubt the state’s claim that its own civilian considerations and needs were not behind the plan.[9]

The conclusion of this case is known: the road (known today as Route 443) ultimately became one of the two main traffic arteries between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, the two largest cities in Israel and in 2000, Israel forbade Palestinians to use it. This prohibition was challenged in the Abu Safiya petition, on which the judgment was given in late 2009.[10] The Supreme Court accepted the petition, determining, inter alia, that it is not within the military commander’s competence as the official in charge of maintaining public order in an occupied territory to impose a permanent and absolute ban on travel by vehicles belonging to residents of the occupied territory, a ban that effectively turns the road into one designated for exclusive travel by vehicles belonging to the citizens of the occupying country.[11] Despite this ruling, the court did permit the military to impose various restrictions on Palestinian travel on the road. The restrictions that were imposed subsequent to the judgment have resulted in a situation wherein, at the time of writing, the number of Palestinians who travel on Road 443 is negligible.[12]

It is interesting to note that the justice who wrote the opinion in Beit Iksa, Justice Vogelman, also wrote the core opinion in Abu Safiya. Armed with the perspective gained in the case of Road 443, Justice Vogelman might have been expected to take the state’s promises about the wonderful miracles that are about to happen to residents of the OPT and their travel options with a grain of salt. Yet the court refuses to do so, despite the chain of events detailed in this commentary and presented to the court itself, a chain of events that clearly shows the sole purpose of the state’s plan is to retroactively gain legitimacy for shifting the route so that it runs through the OPT.

Let us return to the provisions of international law. Article 43 of the Hague Regulations, which many consider as the “mini constitution” of the law of occupation, determines that once governmental powers have been transferred to the occupier, the latter must take every measure necessary to restore and ensure public order and safety, as much as possible, while respecting the laws of the country.[13] This article is designed to reflect a balance between guaranteeing the occupier’s security interests on the one hand, and the needs of the occupied civilian population on the other. That is, in fulfilling its obligations under Article 43, the only interest the occupying power may take into consideration other than its own military needs, is the benefit of the local population.

In a paper authored by Guy Harpaz and Yuval Shani, the two scholars describe how this fundamental principle has been eroded in the judgments produced by the Supreme Court.[14] As the occupation continued and became further and further entrenched, the court began manipulating the law of occupation to get it to match the reality on the ground. Thus, the settlers were gradually added to the population whose needs and interests the military commander must take into consideration. The Supreme Court ruled that the military commander must guarantee the settlers’ security and protect their human rights (such as their right to religious worship), while disregarding the fact that they are prohibited from residing in the OPT under international law.[15] In later judgments, the court goes as far as holding that under Article 43, it is part of the military commander’s duty to ensure the needs of citizens of the occupying power who do not reside in the occupied territory at all. So, for example, as in Abu Safiya, it was held that in order to allow Israelis to travel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem on Road 443, the military commander may impose various restrictions on Palestinian travel on this road.[16]

Thus, the Supreme Court’s case law has turned Article 43 from a legal provision intended to restrain the occupying power to one allowing it ever broader discretion, while bending the laws of occupation further and further. The Beit Iksa judgment blends in with this trend. The document seizing the villagers’ land is titled “order for appropriation for public use”. This title is bitterly cynical when it is clear that the “public” that must pay the price, with the land that provides its livelihood, is not the same “public” that will enjoy the fruits of the seizure.

The court that issued the judgment in Beit Iksa is a tired court. Its attempts over the years to soften the harsh practices employed as part of the occupation, to make them more “user friendly” have become too taxing. The court has no desire to step outside the virtual reality bubble created by the state and examine matters as they really are. Instead, it finds it more convenient to turn to the realm of laches and the allegedly insignificant harm caused to the petitioners. It is easier to avoid confrontation with the State of Israel, the Israel Railway and the residents of Mevassert Zion, a mix of powers and economic interests best not challenged if possible. Those who must pay the price are the residents of Beit Iksa, “protected persons” under international law, but also persons who are vulnerable to the crushing power of the occupier, which receives backing from the court – the same court that should turn the phrase “protected persons” into a reality.

Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel

The author is a lawyer and legal researcher on human rights in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Formerly on staff at HaMoked: Center for the Defence of the Individual.